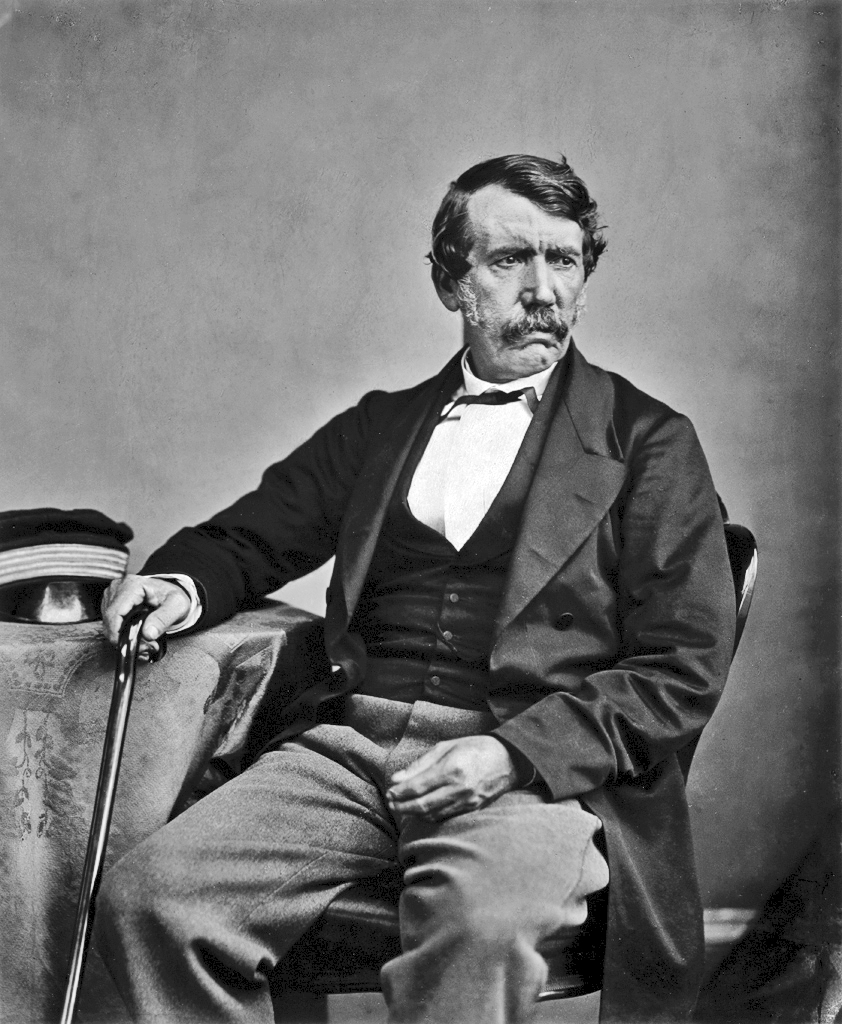

David Livingstone was born to “poor and pious” parents in Blantyre, Scotland, on March 19, 1813. His

father, Neil Livingstone, was a good influence on his family as a “teetotaler, a Sunday school teacher, an

ardent member of a missionary society, and a promoter of prayer meetings,” at a time when few such devout

men were found. As one of the older children in the family, it was necessary for David to go to work in a

factory at age ten. A Latin grammar was purchased out of his first earnings. After working in the factory from

six in the morning until eight at night, with time out for two meals, he attended an evening class from eight to

ten, and his light at home could sometimes be seen still burning at midnight. An avid reader, he would prop

up a book where he could read brief snatches even while at work at his spinning machine.

From time to time from the age of twelve he had earnest thoughts about religion but it was not until he was

twenty years of age that he received Christ’s salvation for himself. His life evidenced great transformation as

he took in the truths of being bought with the blood of Jesus. He understood that the salvation of others

ought to be a chief aim of every Christian, and he made a resolution to support missions as fully as he could.

About a year later, after hearing an appeal on behalf of China where there were many millions needing the

Gospel but a lack of qualified men to give themselves to the task, he felt compelled to give himself to the

work of God in that country. With strong resolve he gave himself to theological training and medical training

in addition to minister to the sick and injured. He lived in strict self-denial the next years as he had to earn

enough in the summer to be able to give himself to the training during the rest of the year. In after years

when he faced much hardship on the mission field, he was grateful for what this hardship during training had

built into his character.

Although he was intending to support himself as a missionary, friends persuaded him to apply to the

London Missionary Society and after some time of probation, he was accepted. To his great disappointment,

the door to China for missionaries was closed at that time due to the opium war. In God’s providence, he

came in contact with Robert Moffat, a Scottish missionary who had labored for twenty-three years in South

Africa, who “fired the soul of his young countryman with a desire to explore and evangelize that ‘dark

continent.’” After obtaining a medical diploma and being ordained a missionary, and bidding his family

goodbye, in December 1840 David Livingstone sailed for Africa.

While traveling on the ship, the captain befriended him and gave him much instruction on the use of the

quadrant, an instrument used in finding the position of a ship from the heavenly bodies. This knowledge later

provided significant help when Livingstone explored in the wilderness of Africa.

Arriving at Algoa Bay on the southeastern shore of South Africa in July 1841, he proceeded promptly to

Kuruman in Bechuanaland (present-day Botswana), the northernmost mission station of the London

Missionary Society. It was here that Mr. Moffat normally resided and ministered, but at this time he was yet in

Britain. Livingstone was instructed to remain there until Mr. Moffat returned. He wrote to a friend at this time,

“Whatever way my life may be spent as best to promote the glory of our gracious God, I feel anxious to do

it…My life may be spent as profitably as a pioneer as in any other way.”

In order to learn the native language, he secluded himself from all European company for about six

months. This gave him valuable insight into the habits, ways of thinking and laws of the natives as well as the

language of the Bakwain people. It was soon evident that Livingstone was effective in working with the

Africans. His medical training helped him greatly to win their acceptance, but he also was careful to show

“genuine kindness and friendliness, good manners, justice and good feeling in his association with them,” all

of which added to his good influence among them. Within a year he could preach in one dialect and was

learning another. Souls were turning to the Lord.

A journey of 700 miles with a fellow missionary confirmed to his thinking that he ought to push into the

interior, into the very heart of heathenism, to establish another station rather than concentrate all efforts at

Kuruman, which was considerably developed after thirty years of missionary endeavor. On his journeyings he

met two foes of evangelizing Africa – fever which attacked men and the tsetse fly which attacked the beasts

of burden and could destroy a whole team of oxen. He made friends with Sechele, chief of the Bakwains,

after successfully treating the chief’s only child and the child of one of his principal men, both of whom were

ill.

After receiving permission from the home authorities of the mission to form a new settlement farther in the

interior, he opened a station at Mabotsa, a beautiful valley surrounded by mountains. This area, unfortunately

however, was infested with lions, which attacked the Africans’ cattle. In helping them seek to kill one of the

lions, which would induce the rest of the troop to leave that area, Livingstone himself shot a lion. However,

before he could reload, the lion sprang on him and caught him by the shoulder and drug him to the ground.

“Growling horribly, he shook me as a terrier dog does a rat,” he said in describing the incident, producing a

sort of shock and stupor. Mebalwe, one of his loyal African co-workers, endeavored to shoot the lion which

turned from Livingstone to the African and bit him. Another man attempted to spear the savage beast and the

lion now turned in his direction. However, by then the bullets had done their work and the lion dropped dead.

Eleven teeth of the lion penetrated Livingstone’s arm. The bones in his arm were “crunched into splinters”

and could not be perfectly set so he was maimed for life in that arm.

About 1844 David Livingstone had the joy of marrying Mary Moffat, the oldest daughter of Robert Moffat

through whose influence he had come to Africa. To them in the next years were born several children. After a

few years at Mabotsa, Livingstone and his family moved further into the interior to Kolobeng, where they

made their home for five years. At each station where Livingstone lived, he had to be both architect and

builder for his home, making his own bricks with the help of the Africans, first cutting trees and sawing out

planks to use as the molds for making the bricks. He was also the gardener, the carpenter and the mechanic,

as well as the medical person and the preacher.

Mary was very able in baking bread in an outside oven, and

making the candles and soap and clothing needed for the family. She also did some teaching and nursing of

the sick. Livingstone said of her that she was “the best spoke in his wheel.” Frugal living was a necessity and

there were times of scarcity. But they lived a happy life together amid the trials and privations, cheerfully and

contentedly serving the Lord. “The joy of the Lord is your strength” (Neh. 8:10).

(To be continued)

– Adapted from The Life of David Livingstone by Mrs. J. H. Worcester, Jr.