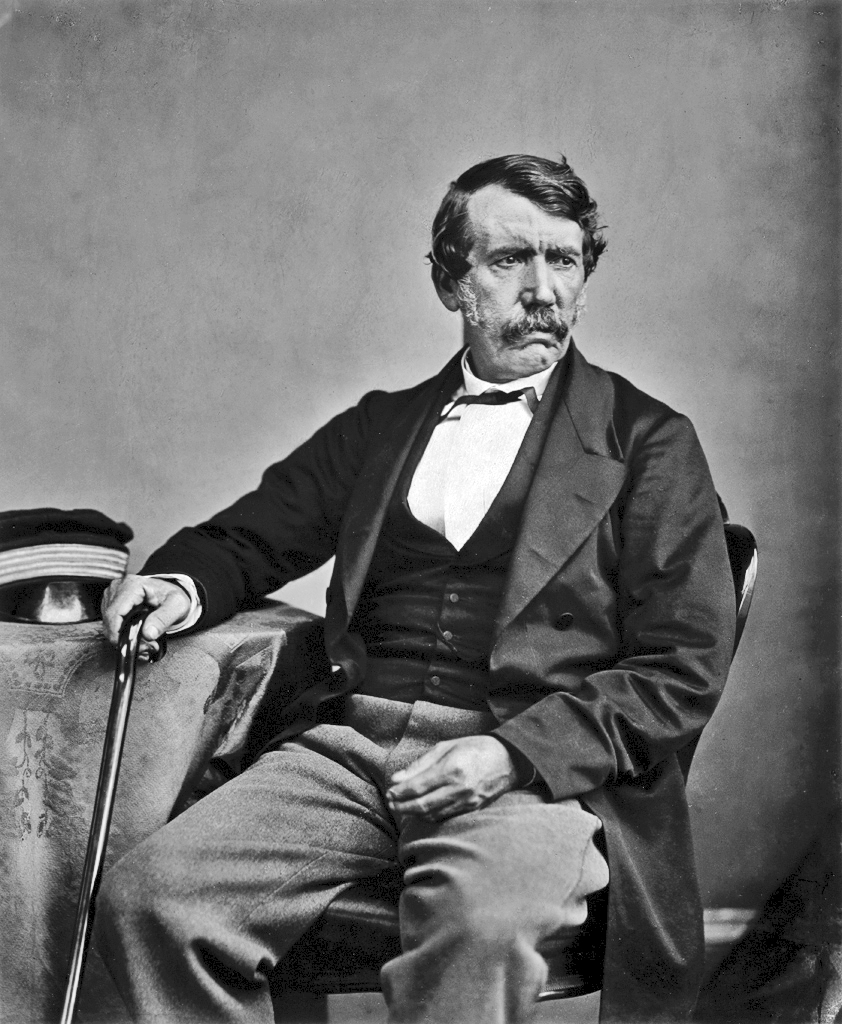

In 1858 David Livingstone, missionary and explorer, returned to Africa from Britain with his beloved wife

and youngest son, pursuing his aim to find a way for the Gospel to enter into the interior of Central Africa,

and a way that would open for legitimate commerce for the area to supplant the frightful but flourishing slave

trade. He felt it God’s leading to accept a position as a counsel to explore the Zambesi River area for the

government. With this new position, there was a new source of funds and he had now a steam launch which

it was hoped would be of much help in exploring the Zambesi River and its tributaries.

Furthermore, his wife could likely travel with him now, to his great anticipation. Instead, however, he experienced grave

disappointment when they arrived in Africa, as the health of his wife prevented her from accompanying him.

It was necessary that she be with her parents, the Moffats, at their station at Kuruman.

Another great disappointment was the performance of the launch which had seemed of great promise but

which was found to be inefficient. Other trials beset them on their expedition, like heat, mosquitoes,

sandbars, and the excessive fuel required to run the launch. Livingstone’s admirable qualities of character

were helpful in maintaining a spirit of perseverance in spite of the drawbacks.

A new steamer arrived in 1861 which was an improvement even if not altogether satisfactory. The expedition did discover beautiful Lake

Nyassa in 1859 and Livingstone saw its importance as the key to Central Africa. The area around Lake

Nyassa and the Shire River valley was suitable for growing cotton and coffee, and it was thought that trade in

these commodities could supplant the slave trade.

About this time God’s good hand of protection upon Livingstone enabled a miraculous escape from a

rhinoceros which was dashing at him. Suddenly it stopped for some unknown reason when close to him,

giving him time to escape!

In 1862 a Christian mission which Livingstone was instrumental in establishing on the Shire tributary of the

Zambesi River and which held great promise in its beginnings was almost broken up by the deaths of several

of those who were successfully operating it. And a greater sorrow followed when his dear wife, who had been

able to join him for a brief three months, succumbed after a short illness. Brokenheartedly he wrote of her

passing, “O, my Mary, my Mary, how often we have longed for a quiet home since you and I were cast adrift

at Kolobeng. Surely the removal by a kind Father who knoweth our frame means that He rewarded you by

taking you to the best home, the eternal one in the heavens…For the first time in my life I feel willing to die.”

It was the grace of God which gave him peace and courage to keep going on, “lonely yet undaunted, ‘faint,

yet pursuing’” (Judg. 8:4).

As he explored, he discovered far more of how deeply the Arab slave trade was entrenched here. In fact,

as he opened up new country, some slave traders followed in his steps, increasing their accessibility to

further victims. He found that the expanse and horror of the slave trade were “beyond exaggeration.” Even

young children were included in the train of slaves being marched to the coast. In a few instances

Livingstone and his party were able to free slaves from their captors, and at least once those gratefully

released chose to join themselves to the Christian mission that had been established. The ill treatment that

some of the enslaved received was horrific. As a medical person he diagnosed that some of those torn away

from family and friends died of a broken heart.

The whole slavery matter pressed hard upon Livingstone. To add to his burden of grief for his dear Mary,

several Europeans in his crew as well as several of the missionaries succumbed to the fever. The placing of

a launch, “Lady Nyassa,” on Lake Nyassa which he had discovered and was set to further explore, was

recalled by the government. He himself struggled with the depression of illness. The Christian mission he

had helped to establish on Shire with highest hopes was abandoned and operations moved elsewhere.

Rather than leave the “Lady Nyassa” launch to fall into the hands of those who would use it for transporting

slaves, he took charge of sailing it across the Indian Ocean 2,500 miles with a crew of three Europeans and

seven Africans who had never before seen the ocean. Arriving eventually in Bombay he sold the launch and

sailed for Britain. Thus ended another phase in Livingstone’s life, one which had held much sorrow and

disappointment.

In Britain he spent a year writing a book on the Zambesi and its tributaries. His co-author was Charles

Livingstone, his brother, who had been with him for part of the expedition. He also took opportunities when

speaking to plead for Africa and the abolishment of the abominable slave trade. While he was in Britain

during this year his “good, dear” mother passed away.

In 1866 he arrived in Africa and again set out with an exploring party of Africans. His aim was still to work

as a missionary along with his explorations. He used the opportunities he had to make known God’s love

manifested in His Son, Christ Jesus, though the Gospel seed sown seemed seldom to take root. He sought

to do what good he could to the natives around him.

In 1867 two of Livingstone’s workers deserted the party taking with them his supply of medicine, which left

him without the protection he needed against the dreaded fever. The fever attacks became more severe and

debilitating. Six weeks of pneumonia took a great toll on him. Time and time again he would find that the

supplies he had ordered from the coast had been looted before he arrived to claim them, leaving him with

scarcely enough food and beverages at times. Little mail from home cheered his heart as many letters were

lost on the way.

Anyone with less patience and endurance than Livingstone’s would have given up hope on the expedition

he had undertaken to find the headwaters of the Nile River as requested by the Geographical Society. As

strength permitted, he pressed on, hoping he could soon complete his purpose and return home. A crowning

disappointment came when his men refused to go farther into the wilderness.

He had no choice but to return 500 miles to the settlement of Ujiji on the shore of Lake Tanganyika, which he had discovered. It proved to be a harrowing trip, as the Africans through whose territories they traveled took him to be a slave trader and

sought to ambush him. Three times in one day he barely escaped death, twice through spears which barely

missed him and once by a falling tree set aflame in hopes it would fall on him.

Several days after his return to Ujiji, the American Henry M. Stanley appeared. He had been sent out by

Mr. J.G. Bennett of the New York Herald, in the interest of a report for his paper. Stanley was as an angel to

Livingstone. “You have brought me new life!” Livingstone repeated to him again and again. Stanley had with

him ample supplies, including medicines, which he put at Livingstone’s disposal and he provided

companionship on a level such as Livingstone had not enjoyed for six years in his wilderness trekkings.

Their hearts were quickly knit together as confidential friends. Stanley bestowed half his clothing on Livingstone,

and shared world news of the past two years of which Livingstone knew nothing. With the additional food,

Livingstone’s strength returned. After four months together it was time for Stanley to return home and he

urged Livingstone to return with him. But Livingstone, though understandably yearning to return, felt he must

fulfill the unfinished task, finding the true sources of the Nile and hoping to suppress the east coast slave

trade.

Stanley said of Livingstone: “For four months and four days I lived with him in the same house, or in the

same boat, or in the same tent, and I never found a fault in him. …Each day’s life with him added to my

admiration for him.”

After their parting, Livingstone wrote a letter to the New York Herald trying to enlist American zeal to put a

stop to the east coast slave trade. He concluded, “All I can add in my loneliness, is, may Heaven’s rich

blessing come down on every one, American, English or Turk, who will help to heal the open sore of the

world.” It was these words written exactly one year before his death, that were inscribed on the tablet erected

to his memory near his grave in Westminster Abbey.

Livingstone asked Stanley to send him some fellows from the coast to accompany him to complete his

purpose. In due time helpers arrived, among them Jacob Wainwright. Wainwright and others with him proved

to be both faithful and capable. As together they set out, they encountered much rain and sickness. In spite

of the hardships, Livingstone wrote, “Nothing earthly will make me give up my work in despair. I encourage

myself in the Lord my God and go forward.”

But at last the sickness and pain and weakness overcame even his remarkable physical endurance and

his indomitable will to accomplish what he felt God had called him to do, however great the cost. Unable to

journey on, he quietly lay for a whole day in a small hut in an African village. Early the next morning, May 1,

1873, he was found by those who were devotedly attending him, on his knees at his bedside as if in prayer,

his head buried in his hands on the pillow, his spirit with the Lord.

Two of Livingstone’s long-time African friends who loved him well, took responsibility to carefully pack all

his possessions including his last journals, for transport back to Britain. His heart was buried in Africa, but his

sun-dried body was carried at great effort to the coast, where a ship took it back to England for burial in

Westminster Abbey.

The Gospel seeds which he diligently sowed have matured, the routes he discovered into the interior have

aided in trade and missionary enterprise, the slave trade was suppressed, and today the African harvest is

being gathered in. To God be the glory! His grace is sufficient!

– Adapted from The Life of David Livingstone by Mrs. J. H. Worcester, Jr